Update: This is part 4 of an ongoing Zero Trust series. See our next post: Zero Trust at GitLab: Implementation challenges (and a few solutions).

Zero Trust is the practice of shifting access control from the perimeter of the organization to the individuals, the assets, and the endpoints. For GitLab, Zero Trust means that all devices trying to access an endpoint or asset within our GitLab environment will need to authenticate and be authorized. This is part four of a multi-part series.

- Part one: The evolution of Zero Trust

- Part two: Zero Trust at GitLab: problems, goals, and coming challenges

- Part three: Zero Trust at GitLab: The data classification and infrastructure challenge

In previous blog posts we’ve covered both the history of the whole Zero Trust Networking (ZTN) scenario, and some of the areas where we expect challenges to successful implementation. In this post we’ll discuss the concept of “data zones” as well as an “authentication scoring system.” The general concept of data zones is not new; it is an established part of a layered security approach where zones of trust are created around groups of data, usually on the same network segment or system. A few things to note:

- Our data zone concept simply groups the data according to access controls available for a system when granular control is not possible.

- Our authentication scoring system is intended to augment our ability to allow access.

- We’ve set up all of our access based upon the team member’s identity and job description, but it should also include information about the device and even the geographic location of the team member (as we shall see later).

Defining data zones

We have previously defined the classification of data to include RED, ORANGE, YELLOW, and GREEN. We’ve also touched on the concept of moving data either via automated or manual means, and data being transformed. Where the data is stored should reflect the classification.

The immediate challenge with regards to data access is when data that is considered RED or ORANGE is stored on a system that has limited access controls, and granting granular access isn’t possible. In other words, we need to define zones where multiple classes of data may reside on a system that is unable to provide separation of access controls based upon our own data classification. The most common scenario will be either a legacy system or a system developed outside of our control, such as a SaaS company offering.

We’ve defined four zones that match the data classifications, and named them after the colors of the data classification:

- RED ZONE for RED and lower data

- ORANGE ZONE for ORANGE and lower data

- YELLOW ZONE for YELLOW and lower data

- GREEN ZONE for GREEN (this may not be needed as it is the lowest classification)

In general, the zones apply to data at rest. Data in transit, either transitioning in system memory between subsystems or transferred over a network between systems, defaults to RED ZONE since access at that level is considered critical. Therefore the ability to access systems at a low enough level to examine RAM or monitoring calls between systems is definitely considered the highest level of restriction, and data moving between systems is subject to the highest levels of encryption.

Here are the basic rules for a zone:

- A zone can contain its own “color” of data or lower, not higher.

- A zone will not allow access to a lower “color” of data within its boundaries without authorization to access the highest designation of “color” for that zone.

- The boundaries of a zone are defined by the access controls specific to that zone.

To illustrate, if a YELLOW ZONE is set up to contain YELLOW data, it cannot contain RED or ORANGE. And while it can contain GREEN data, team members with access to GREEN cannot access that data while it resides in the YELLOW ZONE. In essence, each zone where data resides must have controls that consider what data they might possibly contain.

To explain this further, let’s say that there is a database that contains ORANGE and YELLOW data within it, but the controls in place are not granular – access to the database means access to all of the data contained within it. Therefore this database would be considered ORANGE ZONE, and those with access to only YELLOW data could not be allowed access that data in this database because it is in ORANGE ZONE.

Authentication scoring

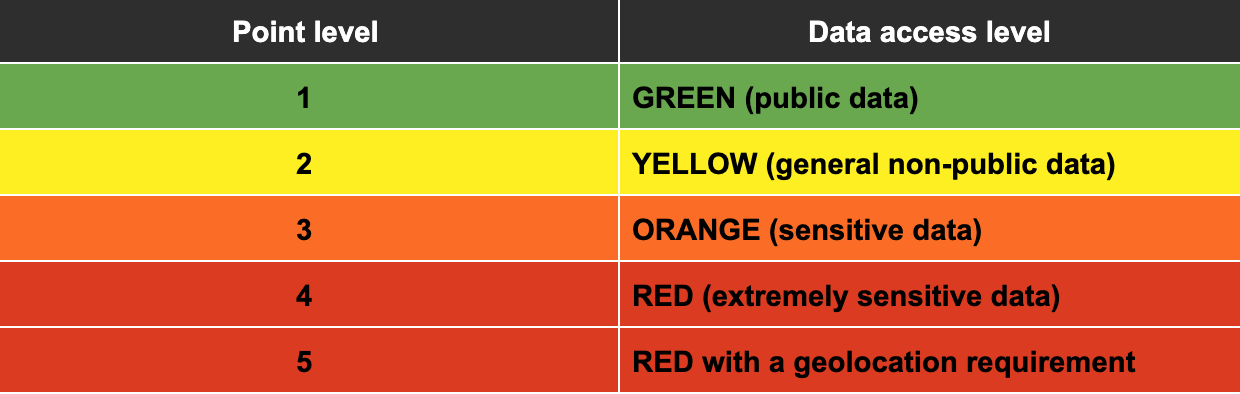

There will be a scoring system for access to data, where a team member is ranked. This isn’t so much an actual system for points, but more of a reference guide on what it takes to be able to access different data.

The earning of points is as follows:

Basic access

One point for basic authentication. This gets you access to the GREEN ZONE and GREEN data.

Basic access with U2F

One point if second factor authentication comes through the proper channel (for GitLab team members that is Okta with approved MFA, such as U2F). Two points are required to access the YELLOW ZONE and YELLOW data, so this, coupled with the previous one point for authentication, allows the access.

Managed device

One more point if the authentication comes via a managed device (a device GitLab has issued to the team member). This is sufficient to allow access to ORANGE ZONE and ORANGE data.

Healthy managed device

If the managed device is in proper health (passes checks for patches, proper configuration, etc) an additional point is given, which allows access to the RED ZONE and RED data. This is not to imply that we will allow “unhealthy devices” to access ORANGE data (for example), but that the requirement is strictly enforced for RED ZONE and RED data.

Geolocation

A final point is given for a managed device with proper health from proper geolocation (this is dependent on the particular RED data being accessed). There may be a requirement that specific data can only be accessed from specific countries, and this is to account for that.

A summary and what’s next

It should be apparent at this point we have a fairly complex situation to administer. We do protect our data but we want more granular control over the access to the data. In a lot of organizations, administrators will end up denying access to parts of their system to employees, and end up having to export portions of the data to those denied access. Additionally, sometimes administrators will grant too much access to employees who simply need to access small segments and do not need the full access.

At GitLab we not only want to avoid that, but we want to document, log, and automate as much of the granular control as possible. This makes other challenges such as onboarding, offboarding, provisioning of access devices, auditing, and other processes much easier. And if it is easier on both the team member and the administrators managing the systems, full adoption is much simpler. The last thing GitLab wants to do is to prevent or curtail the rapid growth we are experiencing.

Designing data zones and coming up with an authentication method to gain access to the data in its zone will help clarify how we want to approach some of the challenges. We have a decent start, but to fully explain how they will need to be applied, we’ll go into a lot more detail in the next post. We’ll also discuss some specific ways to address challenges involving our infrastructure, including the role of managed devices.

Special shout-out to the entire security team for their input on this blog series.