Just over a year ago, Dennis Tang

introduced us to Reviewer Roulette.

This was a shiny new tool designed to help us to find reviewers for our code.

At the time, our engineering department had around 150 people in it. At GitLab,

all our engineers are reviewers,

but reviews were being unevenly distributed across them.

A year on, and with more than 380 people in engineering available to review,

we're still using a form of Reviewer Roulette – but its implementation, and how

we interact with it, has changed significantly. So, what's changed, and what's

stayed the same?

The good

First off, roulette works really well. Code reviews can be time-consuming, and

they're a major part of quality control at GitLab, so it's crucial that we

distribute the load – research shows that review quality nosedives

if you spend too much time doing it. It's even more

important for our maintainers. We try to maintain a ratio of engineers to maintainers of around

4:1, but if half of the reviews go to a quarter of the maintainers, some will

experience it as 6:1, while others will experience it as 2:1.

Also, people could become familiar with certain reviewers and maintainers and

habitually assign their work to the same people. This means that people who had

been maintainers for longer tended to get more reviews. Without the

randomization effect of Reviewer Roulette, this led to the creation of knowledge

silos, where knowledge about a particular subject would be concentrated in a few

individuals, rather than being spread across the organization.

Roulette solved this for us with almost no cognitive load, and could scale

effortlessly as our engineering team expands significantly. Sometimes, I first

learned someone new had joined the company through a review suggestion. The

number and type of reviews a merge request needed was also increasing – I might

need to find a reviewer and maintainer for frontend, backend, QA, database,

documentation, and UX concerns before merging. It's a lot to keep track of

manually!

The bad

Despite the advantages of Reviewer Roulette, I used it inconsistently after a

few months, and never actually contributed any improvements to the code. The

integration with Slack didn't fit my workflow very well because a chat channel

is the last place I want to be when working on code! I like to treat Slack as

the informal, asynchronous communication

channel it is designed to be, but it is too easy to be sidetracked by ongoing

conversations when popping in to get a reviewer recommendation.

Then, we began running into deployment problems, and sometimes Reviewer Roulette

just wasn't available at all. It only took a few failed attempts before I fell

out of the habit of trying to use it, and we never did get around to making the

deployment work with Auto DevOps.

It turns out that I wasn't the only one having trouble with this iteration of Reviewer Roulette – we found

that backend reviews were very unevenly distributed. Reviewer Roulette wasn't being used widely enough across GitLab for us to experience

all the benefits, and as we geared up to add many more maintainers, fixing

this tool became very important.

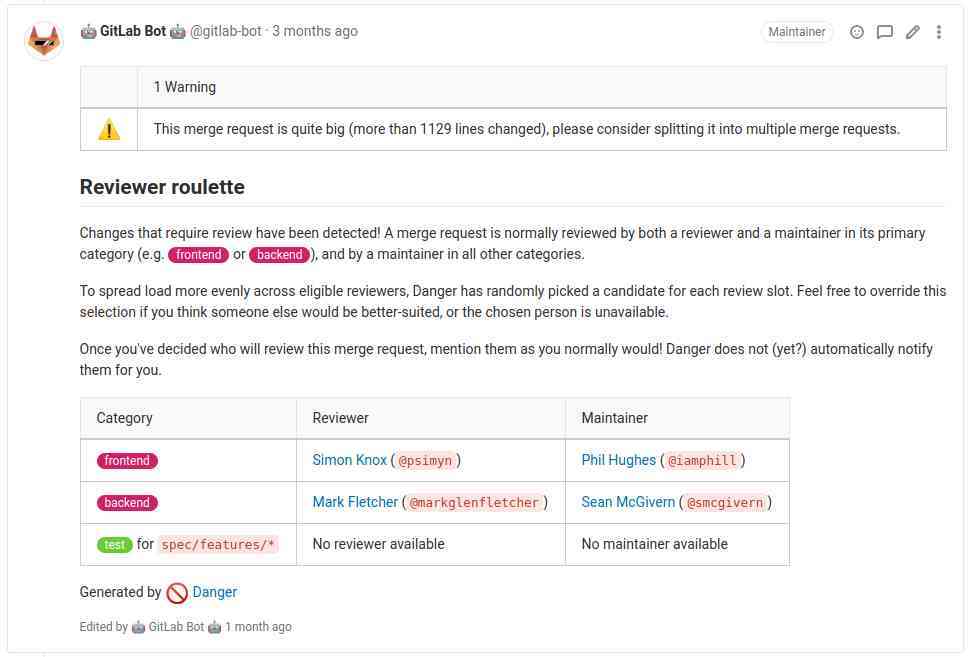

The fix

In the interim, staff backend engineer on Delivery, Yorick Peterse, introduced

Danger bot into GitLab's CI pipeline and

used it to enforce a fine set of coding standards that we couldn't quite express

with Rubocop.

The new bot would leave polite messages on our MRs, asking us to write

better commit messages,

or to seek database review if we'd changed any files in db/. That last part got me

thinking: Why couldn't the Danger bot pick a potential database reviewer for us at the same

time? What was stopping it from detecting backend, frontend, or documentation

changes, and using Reviewer Roulette to choose reviewers and maintainers right there in

the merge request?

By making Reviewer Roulette happen automatically in the merge request itself, we

removed all the barriers that were preventing us from using the tool. I no longer had to be

on Slack to find a reviewer, instead the list was right there in the merge request as

I went to change the assignee. Danger was guaranteed to run on every pipeline –

there were no deployments or environments to worry about, and if it broke,

fixing it was automatically high priority.

Contributing changes also became much easier – the code was right there in the

GitLab repository, and changes took effect immediately (again, no deployments!).

What's next?

The ChatOps version of Reviewer Roulette needed access to GitLab's Slack

workspace to use and so it wasn't available to most of our community contributors

beyond the core team. Moving Reviewer Roulette to Danger doesn't really solve this

problem – it doesn't work well on forks of the gitlab-org/gitlab project so

community contributors don't benefit. This problem is something I'd really

like to fix in the future, not least because I work on a fork of GitLab

day-to-day as well.

Danger is a good tool but it does have some limitations –

in particular, danger local

doesn't work for GitLab. This slows down development, since you have to commit

and push changes to your merge request before you can see the effects.

Another big problem is that this most recent iteration of Reviewer Roulette only

works for the gitlab project. None of our satellite projects - gitaly,

gitlab-workhorse, gitlab-pages, gitlab-runner, etc. – can use this

version of Reviewer Roulette. Similarly, users of GitLab haven't

benefited from the work we've been doing on Roulette.

Ideally, we would have built this as a feature within GitLab itself, so everyone

could benefit from the tool.

By building Reviewer Roulette in Danger we've been able to protype and rapidly iterate

to a solution that is working very well for the gitlab project. The next steps

are to turn Reviewer Roulette into a feature that all users of GitLab can benefit from, perhaps by leveraging the CODEOWNERS file.

Do you have any ideas on how we can better integrate Reviewer Roulette into GitLab? Let us know by commenting in the epic

or by opening a new issue!

Cover photo by Krissia Cruz on Unsplash.