This blog post was originally published on the GitLab Unfiltered blog. It was reviewed and republished on 2020-05-21.

Do you know much about fighter jets? It's okay if you don't, neither did I until I became a software developer. While it seems like a rather strange set of things to see a correlation with, they are intrinsically related through a man named John Boyd who was a military strategist and a fighter pilot.

Boyd was rather famous in the Air Force for a law he coined, which we're going to use to demonstrate the difference between iterative and recursive approaches to software development, why we favor it in the Monitor:Health team and why you might want to favor it too.

Boyd's Law of Iteration states that speed of iteration beats quality of iteration

This law was developed by Boyd while observing dogfights between MiG-15s and F-86s. Even though the MiG-15 was considered a superior aircraft by aircraft designers, the F-86 was favored by pilots. The reason it was favored was simple: in one-on-one dogfights with MiG-15s, the F-86 won nine times out of ten.

What's happening here? If the MiG is the better aircraft, why would the F-86 win the majority of the fights? Well according to Boyd who was one of the best dog-fighters in history suggested:

That the primary determinant to winning dogfights was observing, orienting, planning, and acting faster not better.

This leads to Boyd's Law of Iteration: Speed of iteration beats quality of iteration. What's pretty incredible is that you will find this same scheme throughout every section of modern software development:

- Writing unit tests? Keep them small and lean so they can be run faster.

- Writing usability tests? They work best when they're lean and you can quickly discard what's not working.

- Writing a function, class, or feature? Start with the smallest, most boring solution and iterate.

- Doing an Agile approach? The quicker the better you'll often find.

- Software in general is about failing early and often.

So lets pretend I've convinced you with some obscure fighter jet references and now you're ready to break down those merge requests and iterate quicker than you've ever iterated. Awesome! Let's talk about how to foster a team environment that allows for iteration, because that's the key here at GitLab. When you get started on this pilgrimage to 11 amazing merge requests per month as a goal you need to keep one very important thing in mind:

It's a team effort. While you as an individual developer will do an amazing job by hammering in on this skill, the real difference is made when you look at iteration as a tool to lift the team up. Think of yourself as the pilot that wants to get that faster iteration in to cover your buddies.

Bias for action

When I got started at GitLab I was introduced to the idea of really believing in iteration as a methodology because it's a company value.

Decisions should be thoughtful, but delivering fast results requires the fearless acceptance of occasionally making mistakes.

This was highlighted in various ways by different people across the company, but something that really stuck out to me was hearing another team member refer to the Monitor:Health team as a "team with a strong bias for action". We don't really believe in being reactive, instead we want to be we want to always be proactively improving the product. This underlying belief system trickles down from our team leader into every discussion, decision, deliverable set, and ultimately, how we as developers see our own agency operating. We believe in action, that an open merge request (even if it's not perfect) is always better than nothing.

As we mentioned, we have a bias for action. So, when our team anticipates a problem, we create a merge request first before starting a discussion. I know for a lot of people this might seem a bit counterproductive – what if this is a wasted effort? When in reality, starting at a merge request is the best possible place for any real discussion. It helps create a living log for the conversation, and creates more visibility for the problem we are fixing.

All code is bad code: Impostor syndrome, course correction, and accepting failure

I had a mentor at my old company who was a fantastic programmer, and many of the people on my team looked up to him. One Friday afternoon, he gave a presentation that really shaped my understanding of iteration. This talk, "All code is bad code" became rather famous in our small team because he mostly spoke about why the majority of the code he had written himself was ultimately bad code, and how the desire to appear smart is the number one barrier for people to become great software developers.

What you make with your code is how you express yourself, not the code itself - Eric Elliott

Programming is by its very nature difficult. As humans we're not particularly well-suited for deep and abstract logical thinking – our brains simply don't work like that by default and it's a learned skill for the most part. Being reminded of this is a humbling but freeing experience as it helps you move forward without fear. Every merge request you submit should be high quality but your definition of high quality should shift to mean delivering something useful to an end user.

At GitLab, we accept our limitations in that we might not know everything about the problem we're trying to solve. Instead, we lean heavily into the idea of the smallest, most boring solutions that can be expanded upon quickly by collaborating with our team.

Our bias for action also allows us to course correct quickly.

We always accept there will be uncertainty in what we do as software developers but we don't let that stop us from trying to deliver an amazing product to our users.

When we create a merge request, we do so with a low sense of shame and no ego. This approach allows us to deliver fearlessly even if we're wrong.

As a team, this is the environment you want to foster because it helps create a wonderfully positive feedback loop: Low sense of shame > many merge requests submitted > more discussion > many iterations > ideally, the best possible collaborative results for the end user.

The core takeaway for team leaders is that it's okay to make mistakes. The best thing you can do as a team leader is to foster a safe place for developers to make mistakes and learn as they go.

If you're a developer, remember that it's okay to make mistakes as long as you strive for course correction.

Foster a healthy sense for urgency for writing things down

"While you're thinking about doing it... just do it."

It's one of the things we do so well at GitLab in general it's writing things down. Documenting as we go is how we help our teampick up and go without needing to waste time on unnecessary communication.

It's safe to say that with our GitLab handbook being at 2,500,000 words and counting, the folks here take writing things down pretty seriously.

At GitLab, we believe this is also the path to a higher merge request rate.

On the Monitor:Health team and throughout GitLab believe in preserving our energy, capturing valuable conversations, and making them public to dispense this knowledge widely. As a new team member, I've seen this in action multiple times now. Over the course of my eight weeks at Gitlab, I can count on one hand the number of times I've had to ping a team member with a questions I could not find an answer to in our documentation. The discipline for keeping these notes really keeps the focus on delivering results since we don't have an excess of energy spent going back and forth with questions.

In my first four weeks at GitLab almost every single question I needed a answer to was already covered in the documentation someone else had already gone to the trouble of creating. Here is a list of some of my initial questions and links to the answers in GitLab documentation.

- How do I set up the local GitLab Development Kit?

- How do I set up the GitLab Development Kit with Prometheus?

- How do I use embedded charts via Prometheus and Grafana?

- How do I use the

@gitlab/uicomponents? - How do I handle styling in external projects?

- How should components look and act on pages I am developing?

If you can encourage your team to document solutions as problems arise, it can help developers deliver more.

Documentation is a love letter that you write to your future self. - Damian Conway

Tighten those feedback loops

Keep what works, disregard what doesn't.

You'll often notice that the feedback loop for tight-knit teams just gets tighter over time. People start to see patterns of what does and doesn't work as they work together over time. A good team should aim to address these patterns by keeping the ones that work and refining them but also by not being afraid to disregard the ones that don't work.

Recently, the Monitor:Health team delivered the first iteration of an incident management tool called the Status Page. The team did an amazing job on the Status Page, with each team member really aiming to break problems into their smallest pieces and iterate quickly, which kept the overall merge request rate high for this project.

The post mortem of the development process is what made the biggest different. We came together as a team to discuss what aspects worked well and which aspects didn't with the end goal being to tighten our feedback loops so people can really work autonomously and asynchronously. It takes a lot of bravery to have a critical discussion about what didn't work publicly, and not just focus on all the things you have done well.

How does this play out? Well for us on the Monitor:Health team, it means getting better at refining issues to ensure that when they receive a ready for development label they are truly ready for anyone to pick up at any time and take it all the way to done. This really helps increase the overall merge request rate because developers don't need to sit through one to three feedback loops waiting for their questions to be answered, when they could be getting it done.

For an issue to have a ready for development label it needs to have:

- A clear definition of "done"

- All the necessary conversations are already resolved inside the issue

- Developer defines a clear set of expectations

- Say whether tests are required

- Say whether UX is needed

We are trying to enable any developer on the Monitor:Health team to read an issue with zero preexisting context and deliver a merge request related to the issue without needing to leave that issue. Remember, we're trying to measure results not hours. The less time someone spends asking questions, the more time they can spend delivering results.

Hail to the issue, baby! - Duke Nukem if he was a software developer at GitLab

It's all about the team

The only reason we are able to create this level of velocity inside GitLab is because of the belief that we can and should iterate quickly. By having the support of the team across the main points in how to iterate, i.e., bias for action, low sense of shame, a healthy sense of urgency, and tight feedback loops is the bedrock that allows us to deliver results for customers via a better product.

Well, that's all folks! I hope you enjoyed the read and learned something along the way. If you have any questions or want to suggest an improvement, drop me an email at: [email protected].

When in doubt, iterate faster.

TL;DR, show me the proof

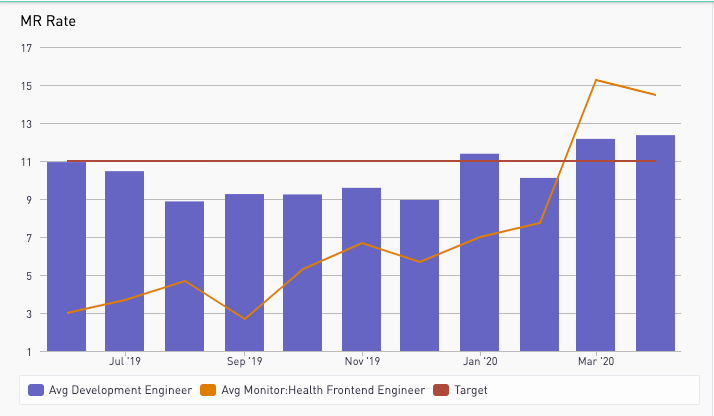

The Monitor:Health frontend team has grown over time while increasing average merge request rate. The team's merge request rate reflects the current team size of four people.

Learn more

We're hiring at GitLab, or consider trying us out for free.

Cover image by Aaron Burden on Unsplash