In Part 1 of this two-part series, we looked at how much server-side Git fetch performance, especially for CI, has improved in GitLab in 2021. Now, we will discuss how we achieved this.

Recap of Part 1

- In December 2019, we set up custom CI fetch caching automation for

gitlab-org/gitlab, which we internally called "the CI pre-clone

script". - In December 2020, we encountered some production incidents on GitLab.com,

which highlighted that the CI pre-clone script had become critical

infrastructure but, at the same time, it had not yet matured beyond

a custom one-off solution. - Over the course of 2021, we built an alternative caching solution

for CI Git fetch traffic called the pack-objects cache. In Part 1,

we discussed a benchmark simulating CI fetch traffic which shows

that the pack-objects cache combined with other efficiency

improvements reduced GitLab server CPU consumption 9x compared to

the baseline of December 2020.

The pack-objects cache

As discussed in Part 1, what we realized through the

production incidents in December 2020 was that the CI pre-clone script

for gitlab-org/gitlab had become a critical piece of infrastructure.

At the same time, it benefited only one Git repository on GitLab.com,

and it was not very robust. It would be much better to have an

integrated solution that benefits all repositories. We achieved this

goal by building the pack-objects cache.

The name "pack-objects cache" refers to git pack-objects, which is

the Git subcommand that

implements the packfile compression algorithm. As this Git commit message from Jeff King explains, git pack-objects is a good candidate for a CI fetch cache.

You may want to insert a caching layer around

pack-objects; it is the most CPU- and memory-intensive

part of serving a fetch, and its output is a pure

function of its input, making it an ideal place to

consolidate identical requests.

The pack-objects cache is GitLab's take on this "caching layer". It

deduplicates identical Git fetch requests that arrive within a short

time window.

At a high level, when serving a fetch, we buffer the output of git pack-objects into a temporary file. If an identical request comes in,

we serve it from the buffer file instead of creating a new git pack-objects process. After 5 minutes, we delete the buffer file. If

you want to know more about how exactly the cache is implemented, you

can look at the implementation

(1,

2).

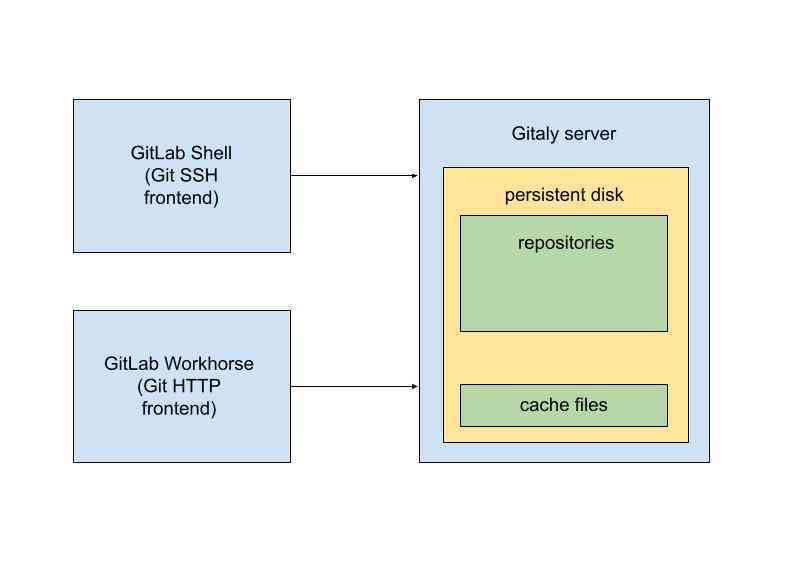

Because the amount of space used by the cache files is bounded roughly

by the eviction window (5 minutes) multiplied by the maximum network bandwidth

of the Gitaly server, we don't have to worry about the cache using a

lot of storage. In fact, on GitLab.com, we store the cache files on the

same disks that hold the repository data. We leave a safety margin of

free space on these disks at all times anyway, and the cache fits in

that safety margin comfortably.

Similarly, we also don't notice the increase disk input/output

operations per second (IOPS) used by the cache on GitLab.com. There

are two reasons for this. First of all, whenever we read data from

the cache, it is usually still in the Linux page cache, so it gets

served from RAM. The cache barely does any disk read I/O operations.

Second, although the cache does do write operations, these fit

comfortably within the maximum sustained IOPS rate supported by the

Google Compute Engine persistent disks we use.

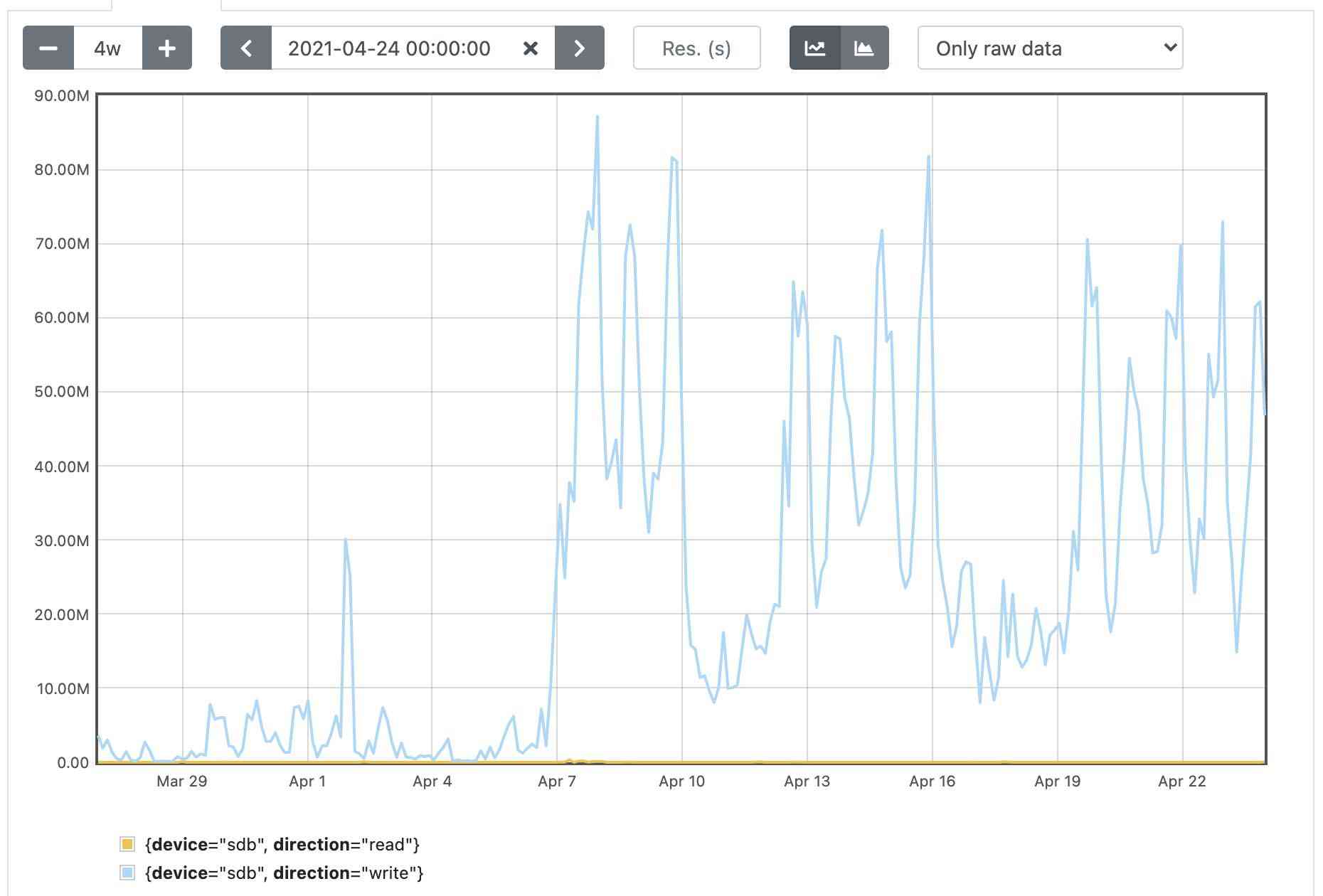

This leads us to a disadvantage of the pack-objects cache, which is

that it really does write a lot of data to disk. On GitLab.com, we saw

the disk write throughput jump up by an order of magnitude. You can

see this in the graph below, which shows disk writes for a single

Gitaly server with a busy, large repository on it: (the GitLab company

website). You can

clearly see the number of bytes written to disk per second jump up when we

turned the cache on.

This increase in disk writes is not a problem for our infrastructure because we have the

spare capacity, but we were not sure we could assume the same for all

other GitLab installations in the world. Because of this, we decided

to leave the pack-objects cache off by default.

This was a difficult decision because we think almost all GitLab

installations would benefit from having this cache enabled. One of the

reasons we are writing this blog post is to raise awareness that this

feature is available, so that self-managed GitLab administrators can

opt in to using it.

Again, on the positive side, the cache did not introduce a new

point of failure on GitLab.com. If the gitaly service is running,

and if the repository storage disk is available, then the cache is

available. There are no external dependencies. And if gitaly is not

running, or the repository storage disk is unavailable, then the whole

Gitaly server is unavailable anyway.

And finally, cache capacity grows naturally with the number of Gitaly

servers. Because the cache is completely local to each Gitaly server,

we do not have to worry about whether the cache keeps working as we

grow GitLab.com.

The pack-objects cache was introduced in GitLab 13.11. In GitLab 14.5,

we made it a lot more efficient by optimizing its transport using Unix

sockets

(1,

2). If

you want to try out the pack-objects cache on

your self-managed GitLab instance, we recommend that you upgrade to

GitLab 14.5 or newer first.

Improved RPC transport for Git HTTP

After we built the pack-objects cache, we were able to generate a much

higher volume of Git fetch responses on a single Gitaly server.

However, we then found out that the RPC transport between the HTTP

front-end (GitLab Workhorse) and the Gitaly server became a

bottleneck. We tried disabling the CI pre-clone script of

gitlab-org/gitlab in April 2021 but we quickly had to turn it back

on because the increased volume of Git fetch data transfer was slowing

down the rest of Gitaly.

The fetch traffic was acting as a noisy neighbor to all the other

traffic on gitlab-org/gitlab. For each GitLab.com Gitaly server, we

have a request latency

SLI. This is

a metric that observes request latencies for a selection of RPCs that

we expect to be fast, and it tracks how many requests for these RPCs

are "fast enough". If the percentage of fast-enough requests drops

below a certain threshold, we know we have a problem.

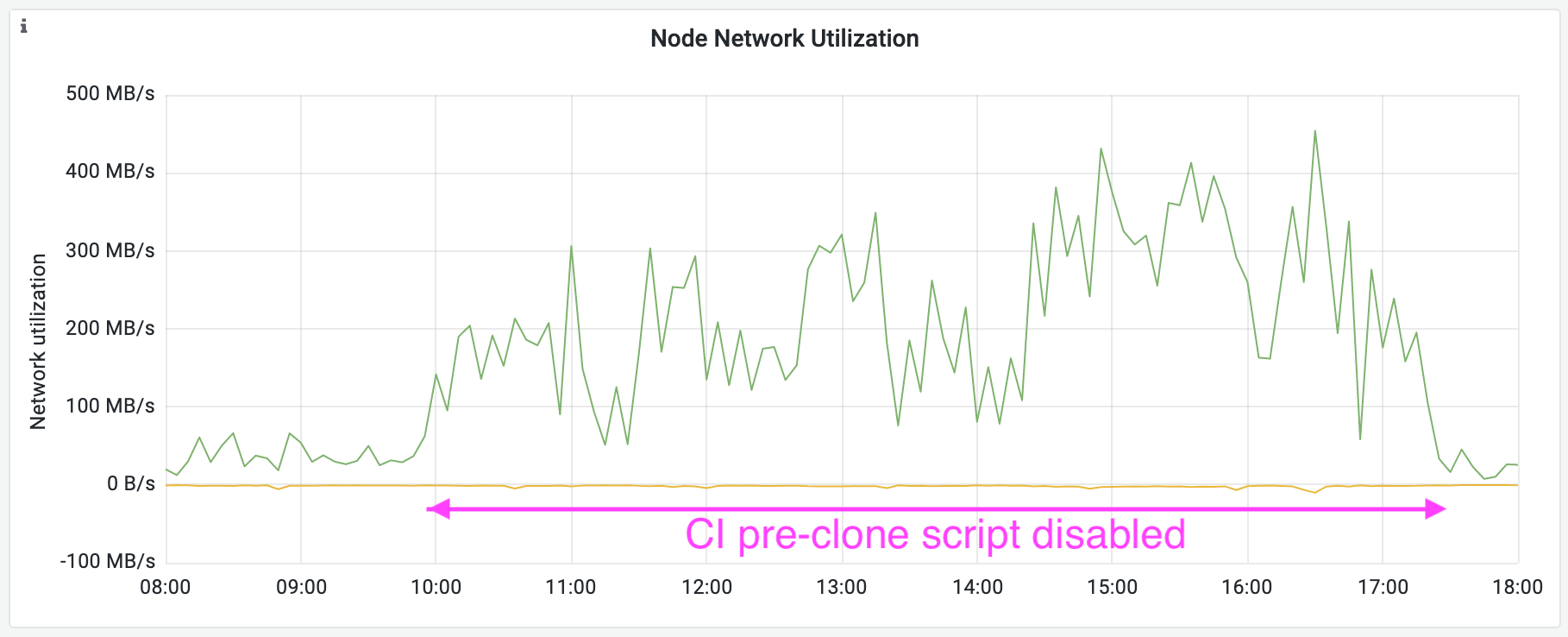

When we disabled the pre-clone script, the network traffic to the

Gitaly server hosting gitlab-org/gitlab went up, as expected. What

went wrong was that the percentage of fast-enough requests started to

drop. This was not because the server had to serve up more data: The

RPCs that serve the Git fetch data do not count towards the latency

SLI.

Below you see two graphs from the day we tried disabling the CI

pre-clone script. First, see how the network traffic off of the Gitaly

server increased once we disabled the CI pre-clone script. This is

because instead of pulling most of the data from object storage, and

only some of the data from Gitaly, the CI runners now started pulling

all of the Git data they needed from Gitaly.

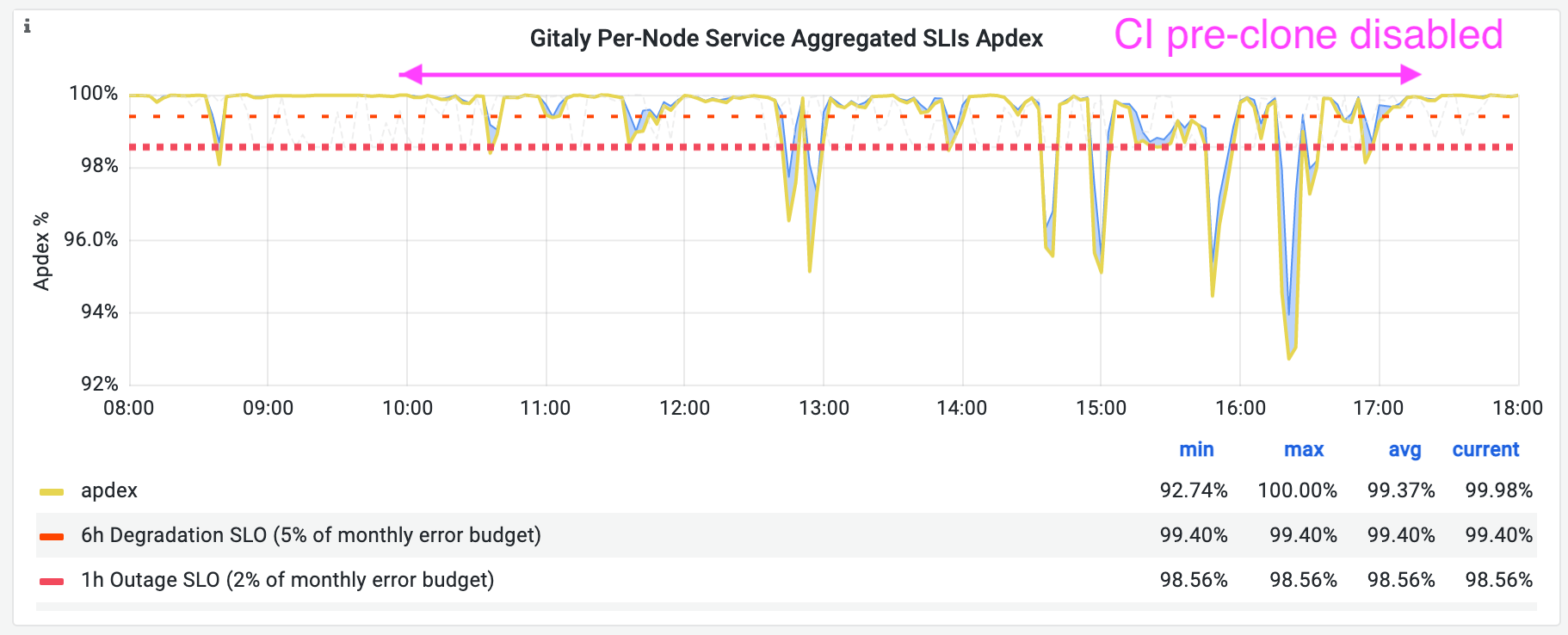

Now consider our Gitaly request latency SLI for this particular

server. For historical reasons, we call this "Apdex" in our dashboards.

Recall that this SLI tracks the percentage of fast-enough requests from

a selection of Gitaly RPCs. The ideal number would be 100%. In the

time window where the CI pre-clone script was disabled, this graph

spent more time below 99%, and it even dipped below 96% several times.

Even though we could not explain what was going on, the latency SLI dips

were clear evidence that disabling the CI pre-clone script slowed down

unrelated requests to this Gitaly server, to a point which is

unacceptable. This was a setback for our plan to replace the CI pre-clone script.

Because we did not want to just give up, we set aside some time to try

and understand what the bottleneck was, and if it could be

circumvented. The bad news is that we did not come up with a

satisfactory answer about what the bottleneck is. But the good news is

that we were able to circumvent it.

By building a simplified prototype alternate RPC

transport,

we were able to find out that with the pack-objects cache, the

hardware we run on and Git itself were able to serve up much more

traffic than we were able to get out of GitLab. We never got to the

bottom

of what was causing all the overhead but a likely suspect is the fact

that gRPC-Go allocates memory for each message it sends, and with Git

fetch traffic we send a lot of messages. Gitaly was spending a lot of

time doing garbage collection.

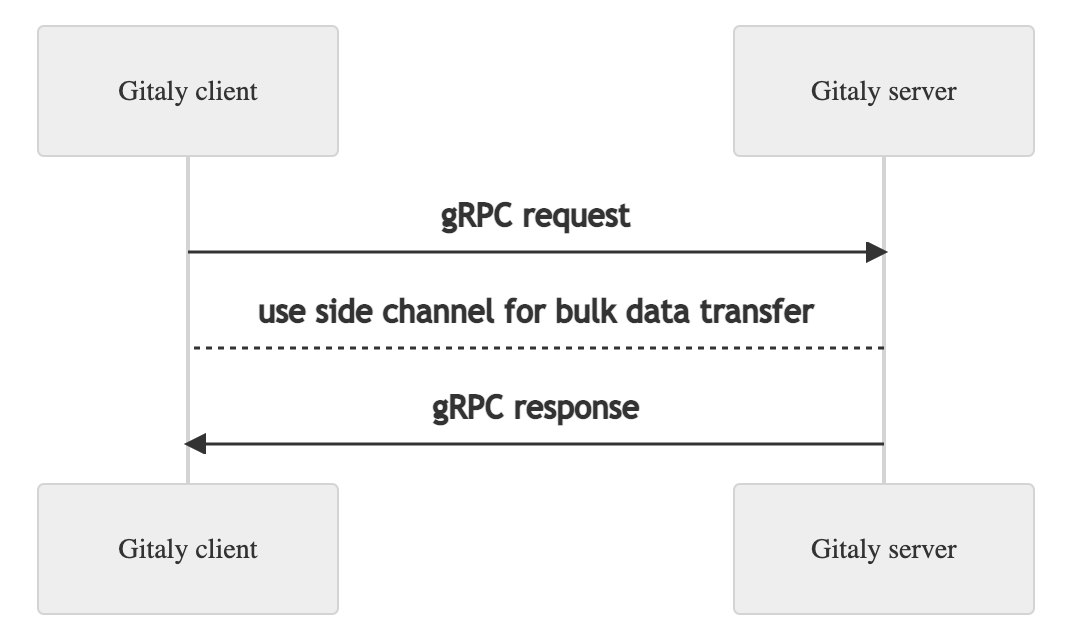

We then had to decide how to improve the situation. Because we were

uncertain if we could fix the apparent bottleneck in gRPC, and because

we were certain that we could go faster by not sending the Git fetch data

through gRPC in the first place, we chose to do the latter. We created

modified versions of the RPCs that carry the bulk of the Git fetch

data. On the surface, the new versions are still gRPC methods. But

during a call, each will establish a side channel, and use that for

the bulk data transfer.

This way we avoided making major changes to the structure of Gitaly:

it is still a gRPC server application. Logging, metrics,

authentication, and other middleware work as normal on the optimized

RPCs. But most of the data transfer happens on either Unix sockets (for localhost RPC calls) or Yamux streams (for the regular RPC calls).

Because we have 6x more Git HTTP traffic than Git SSH traffic on

GitLab.com, we decided to initially only optimize the transport for

Git HTTP traffic. We are still working on doing the same for Git

SSH because, even though Git HTTP efficiency is more important for

GitLab.com than that of Git SSH, we know that for some self-managed

GitLab instances it is the other way around.

The new server-side RPC transport for Git HTTP was released in GitLab

14.5. There is no configuration required for this improved transport.

Regardless of whether you use the pack-objects cache on your GitLab

instance, Gitaly, Workhorse, and Praefect all use less CPU to handle

Git HTTP fetch requests now.

The payoff for this work came in October 2021 when we disabled the CI

pre-clone script for gitlab-org/gitlab, which did not cause any

noisy neighbor problems this time. We have had no issues since then

serving the Git fetch traffic for that project.

Improvements to Git itself

Aside from the pack-objects cache and the new RPC transport between

Workhorse and Gitaly, we also saw some improvements because of changes

in Git itself. We discovered a few inefficiencies which we

reported to the Git mailing list and helped get fixed.

Our main repository gitlab-org/gitlab has hundreds of thousands of Git

references. Looking at CPU profiles, we noticed that a lot of Git

fetch time was spent on the server iterating over these references.

These references were not even being sent back to the client; Git was

just scanning through all of them on the server twice for each CI job.

In both cases, the problem could be fixed by doing a scan over a

subset instead of a scan across all references. These two problems got fixed

(1, 2) in Git 2.31.0, released in March 2021.

Later on, we found a different problem, also in the reference-related

workload of Git fetch. As part of the fetch protocol, the server sends

a list of references to the client so that the client can update its

local branches etc. It turned out that for each reference, Git was

doing 1 or 2 write system calls on the server. This led to a lot of

overhead, and this was made worse by our old RPC transport which could

end up sending 1 RPC message per advertised Git reference.

This problem got fixed in Git itself by changing the functions that

write the references to use buffered

IO.

This change landed in Git 2.34.0, released in November 2021. Ahead of

that, it got shipped in GitLab 14.4 as a custom Git patch.

Finally, we discovered that increasing the copy buffer size used by

git upload-pack to relay git pack-objects output made both git upload-pack and every link in the chain after

it more

efficient. This got fixed in Git by increasing the buffer

size.

This change is part of Git 2.35.0 and is included in GitLab 14.7, both

of which were released in January 2022.

Summary

In Part 1, we showed that GitLab server performance when service CI Git fetch traffic has improved a lot in 2021. In this post, we explained that the improvements are due to:

- The pack-objects cache

- A more efficient Git data transport between server-side GitLab components

- Efficiency improvements in Git itself

Thanks

Many people have contributed to the work described in this blog post.

I would like to specifically thank Quang-Minh Nguyen and Sean McGivern

from the Scalability team, and Patrick Steinhardt and Sami Hiltunen

from the Gitaly team.

Related content

- Improvements to the client-side performance of

git fetch(although GitLab is a server application, it sometimes acts as a Git client): mirror fetches, fetches into repositories with many references - Improvements to server-side Git push performance: consistency check improvements