Recently we finished migrating the GitLab.com monolithic Postgres database to two independent databases: Main and CI. After we decided how to split things up, the project took about a year to complete.

This blog post on decomposing the GitLab backend database is part one in a three-part series. The posts give technical details about many of the challenges we had to

overcome, as well as links to issues, merge requests, epics, and developer-facing documentation.

Our hope is that you can get as much detail as you want about how we work on complex projects at GitLab.

We highlight the most interesting details, but anyone undertaking a similar

project might learn a lot from seeing all

the different trade-offs we evaluated along the way.

- "Decomposing the GitLab backend database, Part 1" focuses on the initial design and planning of the project.

- Part 2 focuses on the

execution of the final migration. - Part 3 highlights some interesting technical challenges we had to solve along the way, as well as some surprises.

How it began

Back in early 2021, GitLab formed a "database sharding" team in an effort to

deal with our ever-growing monolithic Postgres database. This database stored

almost all the data generated by GitLab.com users, excluding git data and some other

smaller things.

As this database grew over time, it became a common source of

incidents for GitLab. We knew that eventually we had to move away from a single

Postgres database. We were already approaching the limits of what we could do

on a single VM with 96 vCPU and continually trying to vertically scale this VM

would eventually not be possible. Even if we could vertically scale forever,

managing such a large Postgres database just becomes more and more difficult.

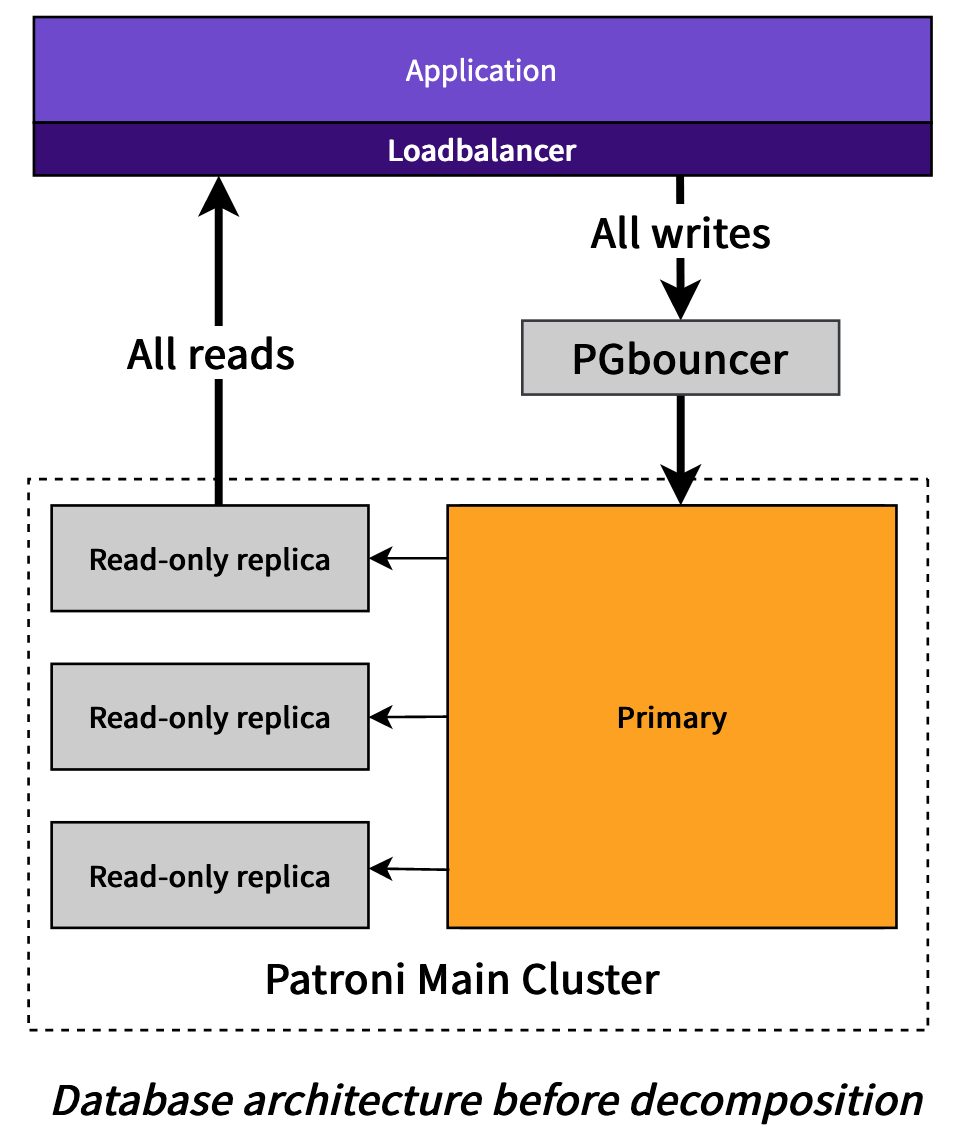

Even though our database architecture has been monolithic for a long time, we already made use of many scaling techniques, including:

- Using Patroni to have a pool of replicas for read-only traffic

- Using PGBouncer for pooling the vast number of connections across our application fleet

These approaches only got us so far and ultimately would never fix the scaling

bottleneck of the number of writes that need to happen, because all writes need to

go to the primary database.

The original objective of the database sharding team was to find a viable way

to horizontally shard the data in the database. We started with exploring

sharding by top-level namespace. This approach had some very complicated problems to solve, because the application

was never designed to have strict tenancy boundaries around top-level

namespaces. We believe that ultimately this will be a good way to split and

scale the database, but we needed a shorter term solution to our scaling

problems.

This is when we evaluated different ways to extract certain tables into a

separate database. This approach is often referred to as "vertical

partitioning" or "functional decomposition." We assumed this extraction would likely

be easier, as long as we found a set of tables with loose coupling to the rest

of the database. We knew it would require us to remove all joins to the rest of the

tables (more on that later).

Figuring out where most write activity occurs

We did an analysis of:

- Where the bulk of our data was stored

- The write traffic (since ultimately the number of writes was the thing we were trying to reduce)

We learned that CI tables (at the time) made up around 40% to 50% of our write traffic. This seemed like a

perfect candidate, because splitting the database in half (by write traffic) would be

the optimal scaling step.

We analyzed the data by splitting the database the following ways:

| Tables group | DB size (GB) | DB size (%) | Reads/s | Reads/s (%) | Writes/s | Writes/s (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Webhook logs | 2964.1 | 22.39% | 52.5 | 0.00% | 110.0 | 2.82% |

| Merge Requests | 2673.7 | 20.20% | 126073.4 | 1.31% | 795.4 | 20.40% |

| CI | 4725.0 | 35.69% | 1712843.8 | 17.87% | 1909.2 | 48.98% |

| Rest | 2876.3 | 21.73% | 7748488.5 | 80.82% | 1083.6 | 27.80% |

Choosing to split the CI tables from the database was partly based on instinct.

We knew the CI tables (particularly ci_builds and

related metadata) were already some of the largest tables in our database. It

was also a convenient choice because the CI tables were already prefixed with

ci_. In the end, we realized only three tables were CI tables that weren't

prefixed with ci_. You can see the up-to-date list of tables and their respective

database in gitlab_schemas.yml.

The next step was to see how viable it actually was.

Proving it can work

The first proof-of-concept merge request was created

in August 2021. The proof-of-concept process involved:

- Separating the database and seeing what broke

- Fixing blockers and marking todo's until we ended up with the application "pretty much working"

We never merged this proof of concept, but we progressively broke out changes into smaller merge requests

or issues assigned to the appropriate teams to fix.

Chasing a moving target

When tackling a large-scale architecture change, you might find

yourself chasing a moving target.

To split the database, we had to change the application. Our code depended on all

the tables being in a single database. These changes took almost a year.

In the meantime, the application was constantly evolving

and growing, and with contributions from many engineers who weren't necessarily

familiar with the CI decomposition project. This meant that we couldn't just

start fixing problems. We knew we would likely find new problems being

introduced at a faster rate than we could remove them.

To solve this problem, we took an approach that was inspired by

how we handle new RuboCop rules.

The idea is to implement static or dynamic analysis to detect these

problems. Then we use this information to generate an allowlist of exceptions.

After we have this allowlist of exceptions, we prevent any new violations from being created

(as any new violations will fail the pipeline).

The result was a clear list to work on and visibility into our progress.

As part of making the application compatible with CI decomposition, we needed to

build the following:

- Multiple databases documentation taught

developers how to write code that is compatible with multiple databases. - Cross-join detection analyzed all SQL queries

and raised an error if the query spanned multiple databases. - Cross-database transaction detection

analyzed all transactions and raised an error if queries were sent to two

different databases within the context of a single transaction. - Query analyzer metrics analyzed all SQL queries

and tracked the different databases that would be queried (based on table

names). These metrics, which were sampled at a rate of 1/10,000 queries, because they are

expensive to parse, were sent to Prometheus. We used this data to get a sense

of whether we were whittling down the list of cross-joins in production.

It also helped us catch code paths that weren't covered by tests but were

executed in production. - A Rubocop rule for preventing the use of

ActiveRecord::Baseensured that we always

used an explicit database connection for Main or CI.

Using Rails multiple database support

When we began this project, there were many improvements being added to Rails to

support multiple databases. We wanted to make use of as much of this Rails

built-in support as possible to minimize the amount of custom database

connection logic we had to maintain.

One considerable challenge with this was our existing

custom database load balancing logic.

The development of this complex implementation spans a long period of time, and

it was designed differently to how Rails connections were managed in the new

multi-database support.

In the end, were able to use parts of Rails multiple database support, but

we still hope to one day remove our custom logic and only use what is supported by Rails.

Implementing loose foreign keys

There were still some foreign keys that existed between CI and non-CI tables.

We needed a way to remove these keys but still keep the functionality of cascading

deletes.

In the end, we implemented a solution

we call "loose foreign keys". This solution provides similar functionality and

support for cascading NULLIFY or DELETE when a parent record is deleted in

Postgres. It's implemented using Postgres on delete triggers, so it guarantees all

deletes (including bulk deletes) will be handled. The trigger writes to another

"queue" table in Postgres, which then is picked up by a periodic Sidekiq worker

to clean up all the impacted child records.

When implementing this solution, we also considered the option of using

ActiveRecord before_destroy callbacks.

However they couldn't give us the same guarantees as Postgres foreign keys,

because they can be intentionally or accidentally skipped.

In the end, the "loose foreign keys" solution also helped to solve another problem

we have, where very large cascading deletes cause timeouts and user experience issues.

Because it's asynchronous, we could easily control timing and batch sizes to never

have database timeouts and never overload the database with a single large

delete.

Mirroring namespaces and projects

One of the most difficult dependencies between CI and Main features in GitLab

is how CI Runners are configured. Runners are assigned to projects and groups

which then dictates which jobs they will run. This meant there were many join

queries from the ci_runners table to the projects and namespaces tables.

We solved most of these issues by refactoring our Rails code and queries, but

some proved very difficult to do efficiently.

To work around this issue, we implemented a mechanism to

mirror the relevant columns on projects and namespaces to the CI database.

It's not ideal to have to duplicate data that must be kept up-to-date like

this, but while we expected this may be necessary in a few places, it turns out

that we only ended up doing this for those two tables. All other joins could be

handled without mirroring.

An important part of our mirroring architecture is periodic

consistency checking.

Every time this process runs, it takes a batch of the mirrored rows and compares them

with the expected values. If there is a discrepancy, it schedules them to be fixed.

After it's done with this batch, it updates a cursor in Redis to be used for the

next batch.

Creating a phased rollout strategy

A key part of ensuring our live migration went as smooth as possible was by

making it as small as possible. This was quite difficult as the migration from

1 database to 2 databases is a discrete change that seems hard to break up into

smaller steps that can be rolled out individually.

One early insight was that we could actually reconfigure GitLab.com ahead of

time so that the Rails application behaved as though it was talking to two

separate databases long before we actually split the databases. Basically the

idea was that the Rails processes already had two separate database connections,

but ultimately they were going to the same database. We could even break things

out further since our read-only connections are designed to read from slightly

delayed replicas. So we could already have read-only connections going to the

newly created CI read-only replicas before the migration.

These insights led to our seven-phase migration process.

This process meant that by the time we got to the final migration on production

(Phase 7), we were already incredibly confident that the application would work

with separate databases and the actual change being shipped was just trivial

reconfiguration of a single database host. This also meant that all phases

(except for Phase 7) had a very trivial rollback process, introduced very

little risk of incident and could be shipped before we were finished with every

code change necessary to make the application support two databases.

The seven phases were:

- Deploy a Patroni cluster

- Configure Patroni standby cluster

- Serve CI reads from CI standby cluster

- Separate write connections for CI and Main (still going to the same primary host)

- Do a staging dry run and finishing the migration plan

- Validate metrics and additional logging

- Promote the CI database and send writes to it

Using labels to distribute work and prioritize

Now that we had a clear set of phases we could prioritize our work. All issues

were assigned scoped labels

based on the specific phase they corresponded to. Since the work spanned many

teams in development and infrastructure, those teams could use the

label to easily tell which issues needed to be worked on first. Additionally,

since we kept an up-to-date timeline of when we expected to ship each phase,

each team could use the phase label to determine a rough deadline of when that

work should get done to not delay the project. Overall there were at least 193

issues over all phases. Phase 1 and 2 were mostly infrastructure tasks tracked

in a different group and with different labels, but the other phases contained

the bulk of the development team requirements:

Continue reading

You can read more about the final migration process and results of the migration in Part 2.