This blog post is part 2 in a three-part series about decomposing the GitLab backend database. It focuses on the final migration

process and highlights the results we achieved after the migration. If you want to read about the design and planning phase, check out part 1.

Deciding between zero downtime and full downtime

Early on in the project we thought it would be necessary for the migration to

be "zero downtime" or "near-zero downtime". We came up with this plan

early on which involved (in summary):

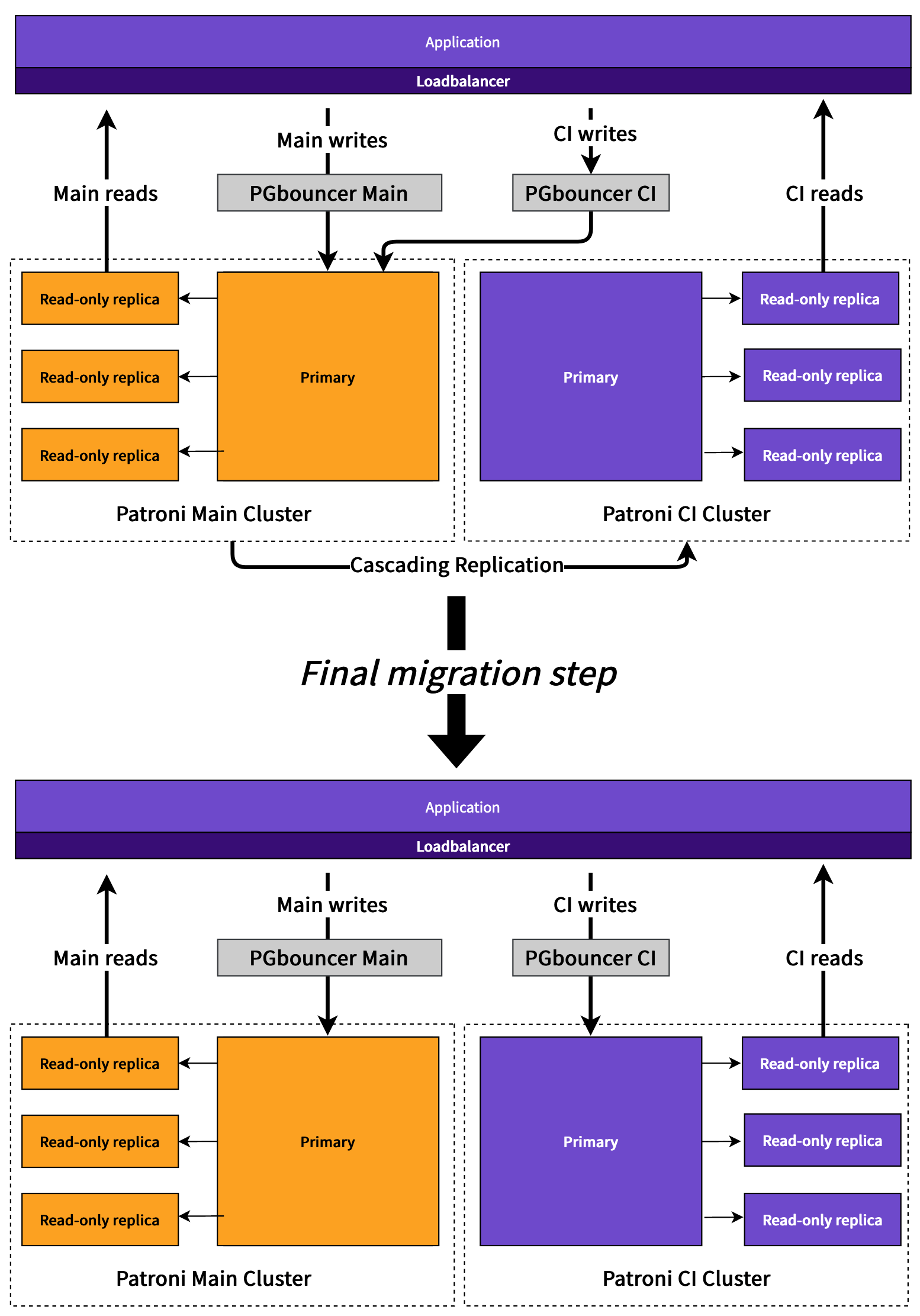

- The entire database would be replicated (including non-CI tables) using

Patroni cascading/standby replication to a dedicated CI Patroni cluster.

Replication only lags by at most a few seconds. - Read traffic for CI tables could be split ahead of time to read from the CI

replicas. - Write traffic would be split ahead of the migration into CI and Main by

sending these through separate dedicated PGBouncer proxies. Initially CI

writes still go to the Main database since the CI cluster is just a standby.

These proxies would be the thing we reconfigured during the live migration

to point at the CI cluster. - At the time of migration we would pause writes to the CI tables by pausing

the CI PGBouncer. - After pausing writes to the CI database we'd capture the current LSN

position in Postgres of the Main primary database (now expect no more writes

to CI tables to be possible). - After that we wait until the CI database replication catches up to that

point. - Then we promote the CI database to accept writes (remove the cascading

replication). - Then we reconfigure writes to point to the CI database by updating the write

host in the CI PGBouncer. - The migration is done.

This approach (assuming that the CI replicas were only delayed by a few

seconds) would mean that, at most, there would be a few seconds where CI writes

might result in errors and 500s for users. Many failures would likely already

be retried since much of CI write traffic goes via asynchronous (Sidekiq)

processes that automatically retry.

In the end we didn't use this approach because:

- This approach didn't have an easy-to-implement rollback strategy. Data that

was written to CI tables during the migration would be lost if we rolled

back to just the Main database. - The period of a few seconds where we expect to see some errors might make it

difficult for us to quickly determine the success or failure of the

migration. - There was no hard business requirement to avoid downtime.

The migration approach we ended up using took two

hours of downtime. We stopped all GitLab services that could read or write

from the database. We also blocked user-level traffic at the CDN (Cloudflare) to allow us

to do some automated and manual testing before opening traffic back up to

users. This allowed us to prepare a slightly more straightforward rollback procedure,

which was:

- Reconfigure all read-only CI traffic back to the Main replicas

- Reconfigure all read-write CI traffic (via PGBouncer) back to the Main

primary database - Increment the Postgres sequences for all CI tables to avoid overlapping with

data we created in our testing

Ultimately having a simple rollback mechanism proved very useful in doing many

practice runs on staging.

Rehearsing the migration process

Before executing the final migration on GitLab.com, we executed seven rehearsals

with rollback and one final migration on our staging environment. In these

practice runs, we discovered many small issues that would have likely caused

issues in the production environment.

These rehearsals also gave all the participants an opportunity to perfect their steps

in the process to minimize delays in our production rollout. This practice

ultimately allowed us to be quite confident in our timeline of at most two hours of downtime.

In the end, we finished the migration in 93 minutes, with a few small delays caused by

surprises we did not see in staging.

The rehearsal process was very time-consuming and a vast effort to execute in

the context of GitLab, where we all work

asynchronously

and across different timezones. However, it proved to be essential to the success of

this project.

Preparing for production migration

One week before our the final migration on production we prepared a production

readiness review issue for final approval from executives. This was a good

opportunity to highlight all the preparation and validation we'd done to give

us confidence in the plan. This also encouraged us to do extra validation where

we might expect to see questions or concerns about the plan.

Some highlights from this review included:

- The amount of practice runs we'd done including details about the problems

we'd seen and resolved in staging - Metrics which we'd observed to prove all the queries were using the right

database connections already - Details about how long we'd been running without issues in local development

with all GitLab developers running with two databases by default - Details about the rollback strategy we would use if necessary and how we

tested this rollback strategy in staging as well as some production

validation

Tracking the results

After we completed the rollout we tracked

performance improvements across some metrics we expected to improve.

The data showed:

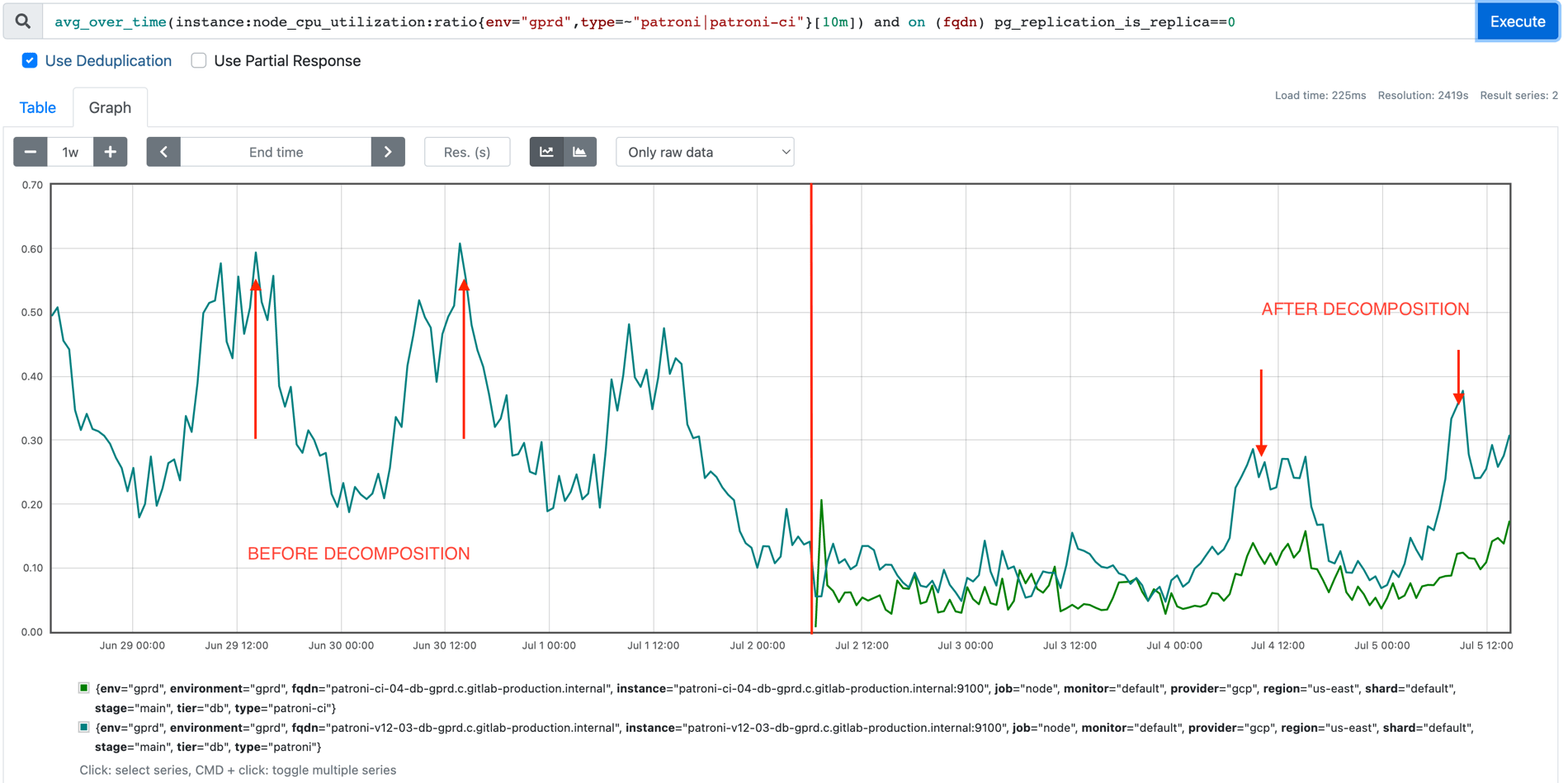

-

We decreased the CPU utilization of our primary database server, giving us much more headroom.

-

We can free around 9.2TiB out of 22TiB from our Main database by truncating the CI tables.

-

We can free around 12.5TiB out of 22TiB from our CI database by truncating the Main tables.

-

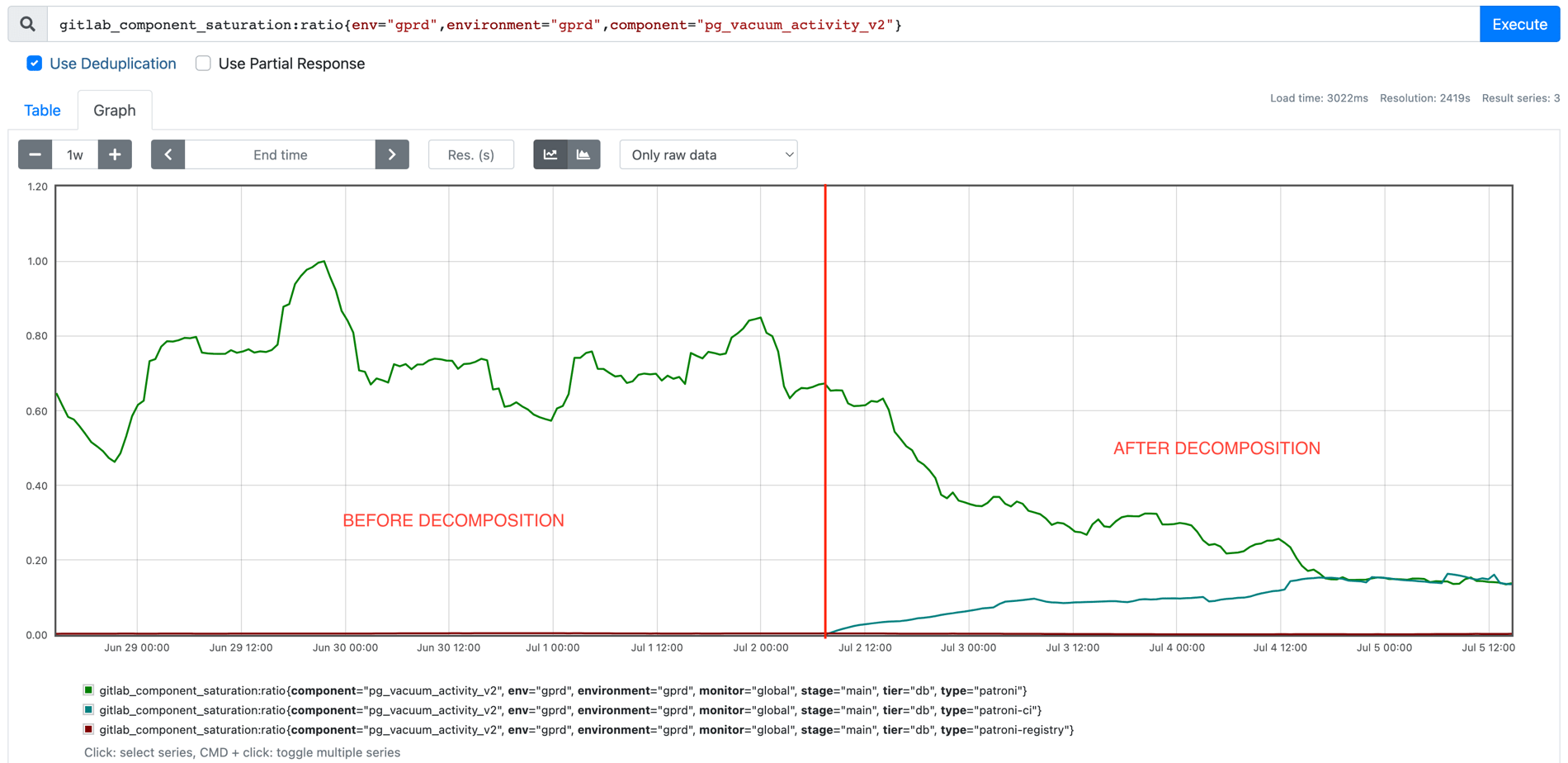

We significantly reduced the rate of dead tuples on our Main database.

-

We significantly reduced vacuuming saturation. Before decomposition the Main database

maximum vacuuming saturation was up to 100%, with the average closer to 80%. After

decomposition, vacuuming saturation has stabilized at around 15% for

both databases.

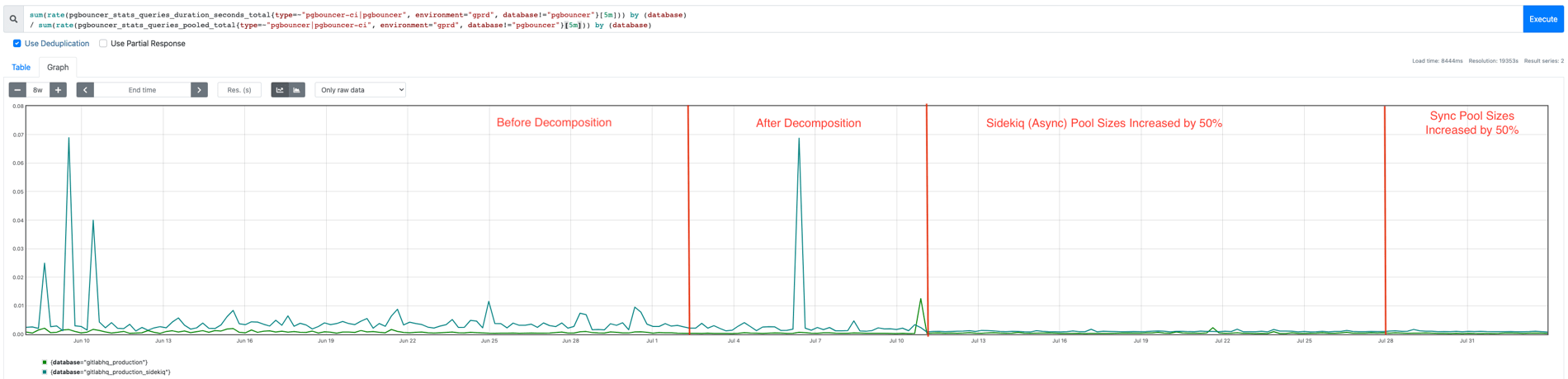

-

We reduced the average query duration for our Sidekiq PGBouncer query

pool by at least a factor of 5 once we scaled up connection limits due to our

increased headroom. Previously we needed to throttle connections for

asynchronous workloads to avoid overloading the primary database.

Continue reading

You can read more about some interesting technical challenges and surprises we

had to deal with along the way in

part 3.